Managers of big mutual funds seldom expose their stock-laden portfolios to the highly illiquid private markets, but some of the fund industry’s biggest players have drawn scrutiny in recent years for aggressive bets on some of Silicon Valley’s boldest unicorns.

A series of flops by high-profile venture-backed companies journeying to the IPO market this year is a telling reminder of the risks that fund managers have accepted by blending a few high-flying private assets with their more staid publicly traded stocks.

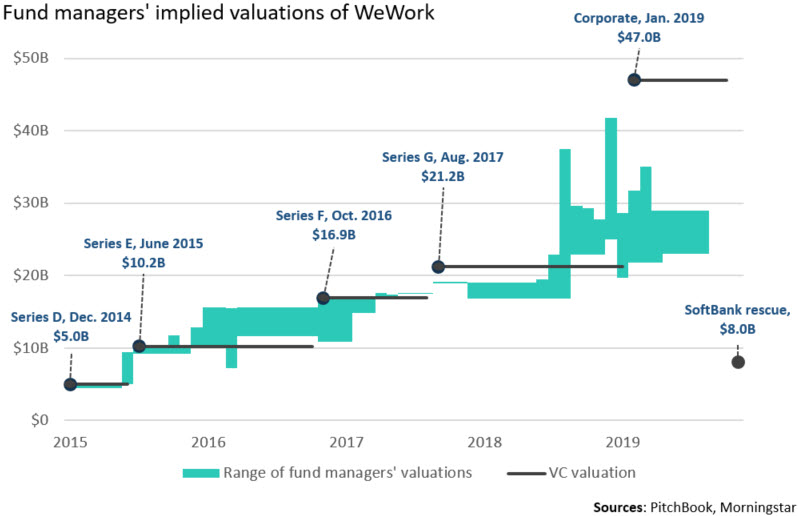

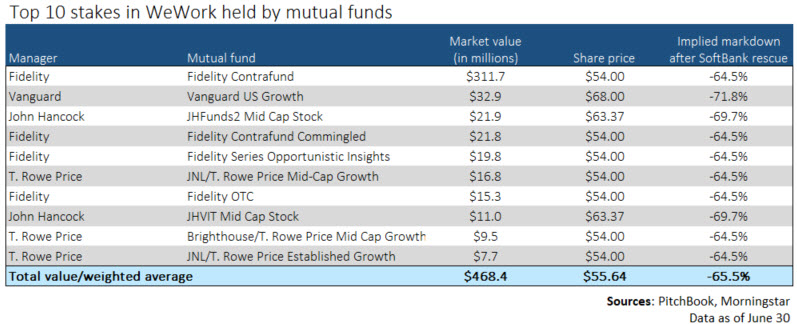

WeWork‘s disastrous attempt at going public is the latest and most dramatic data point yet for widely held mutual fund companies like Fidelity, Vanguard and John Hancock that tagged lofty valuations on their shares in the co-working space provider. As of June 30, the top 10 mutual funds collectively owned WeWork shares worth almost $470 million, based on the fund managers’ valuations, according to a PitchBook analysis of the most recent data available for that period.

Now those valuations are poised for a massive downward adjustment.

To stave off a cash crisis, WeWork is currently on life support after accepting a rescue package of financing from SoftBank that comes with a new valuation of $8 billion, or $19.19 a share.

That’s a small fraction of the lofty levels that SoftBank and other investors placed on WeWork in late 2018—long before the company’s doomed IPO.

Fund managers, however, have attached a wide range of valuations to WeWork. Hartford, John Hancock, and Principal put the company at an implied value of $42 billion, or $110 a share, in November of last year. Meanwhile, T. Rowe Price and Fidelity, the largest US fund manager, had implied valuations of $25 billion and $28 billion, respectively.

It’s unclear whether mutual funds sold any of their WeWork shares as part of SoftBank’s new financing. Later this month, fund managers are expected to begin disclosing their updated statements on their portfolio holdings as of Sept. 30—weeks before SoftBank took control of WeWork.

Most funds tend to shy away from private assets in part because of their need to maintain enough liquidity to accommodate a potential wave of investors seeking redemptions.

Only 5.8% of funds held some form of private assets as of December 2017, according to a study by fund tracker Morningstar. (PitchBook is a Morningstar company.) Those that do make private investments usually have well under 5% of their portfolio exposed to such companies, and that figure is capped by regulators at a maximum of 15%.

Fidelity, T. Rowe Price and Hartford funds in recent years have made the industry’s biggest commitments to private-market shares, as managers sought higher returns in an era with fewer new stocks coming onto the public markets. Since 2015, that has led fund managers to buy into many of Silicon Valley’s hottest, high-growth startups like Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, Pinterest and Slack.

Representatives of Fidelity, John Hancock, T. Rowe Price and other big mutual funds holding WeWork shares declined to comment about individual stocks in their portfolios. But they said that investment committees using proprietary methods establish the fund company’s price benchmarks and review them on a quarterly basis. SoftBank didn’t respond to a request for comment.

After this article was published, T. Rowe issued a statement saying the private markets are a “natural extension of our core investment process” and the company subjects all its potential investments to the same due diligence process. T. Rowe also acknowledged that private market deals are inherently riskier than publicly traded stocks.

“Our long-term focus and patience is one reason we believe we are a good ‘owner’ for private companies,” T. Rowe said.

Mutual fund managers making such investments are walking a fine line between traditional fund management and more aggressive, riskier forms of alternative investments outside their core competency, said Derek Hageman, a financial analyst with the American Association of Individual Investors, an educational group based in Chicago.

“They’re not VCs. They’re not PE investors. They’re mutual funds,” Hageman said.

To be sure, although fund managers are bracing for a mighty markdown on their WeWork stakes, such shares make up a relatively small allocation in heavily diversified portfolios, so their overall negative impact is limited.

Fidelity’s Contrafund, a large-growth fund with assets of almost $115 billion, initially invested about $214 million in WeWork in 2015 with a purchase of 6.5 million shares at $32.89 apiece, according to Contrafund’s monthly fund disclosure.

More than a year later, the fund added 2.2 million shares priced at $50.19 and then took some profits with two separate rounds of share sales, resulting in a realized gain of about 58%. Factoring in WeWork’s newest financing and a share price of $19.19, Contrafund’s shares are facing a 43% discount to their original purchase price. Even with realized gains from earlier partial sales, Contrafund still faces a loss of 29% on its overall position since its entry into WeWork.

All the while, Contrafund currently has an 18% return year-to-date, according to Morningstar. Other notable private companies in Contrafund’s portfolio as of Aug. 30 included vacation rentals platform Airbnb, genetic-testing specialist 23andMe and direct-to-consumer shoe company Allbirds.

The results look a bit rosier at Vanguard’s US Growth Fund, which first bought 517,000 shares of WeWork at a more appealing entry point of $16.65. Vanguard already has sold 33,000 shares at $51.81, but its last available valuation put its WeWork shares at $68, which would represent an unrealized loss of 72%, assuming a newly reset valuation of $19.19 per share.

In light of Wall Street’s sour reception of deals this year from the likes of WeWork, Uber and Peloton, fund managers may see some fresh criticism about whether they applied adequate screening of private assets in line with industry practices.

“Even if a fund manager invests a relatively modest amount of capital in private placements, the kinds of companies that manager invests in says something about his or her process,” said Alec Lucas, a senior analyst with Morningstar.

He said that enough concerns had emerged about WeWork’s business model that “one has reason to question the level of due diligence” and judgment the funds have applied.

“Even the best active managers make mistakes,” said Lucas, “but some mistakes are more telling than others. Investing in WeWork is a telling mistake.”